J-Lit Review #7: Inheritors

A sprawling narrative across multiple generations told in very different short stories.

The owner of my local bookshop suggested I read Asako Serizawa’s Inheritors as she knows I’m a huge fan of contemporary Japanese literature. To be honest, when I read the synopsis, I was tempted to put the book back on the shelf because I don’t generally enjoy sprawling intergenerational narratives. Sure, there are many examples in classic literature of such works, but they’re not to my personal taste. Thankfully, after flicking through a few pages, I decided this looked different and gave it a shot.

First of all, this is not a traditional novel and it’s not told in chronological order. It’s not a dull slog of a book that takes you from the great-grandparents down to the latest generation. Instead, it’s more like a series of interconnected short stories about people who are related. They’re all of Japanese ancestry with some of them now living in America. Some stories take place in the early 20th century and others are from the near future.

What I most like about this book is the fact that Serizawa has written each story in a different style. I mentioned one about the future, which of course comes from the science fiction genre. Another story is just one side of an interview, with the reader left guessing the interviewer’s questions. Elsewhere we have fragments of evidence in a criminal investigation. She clearly likes to explore different perspectives, themes, forms, and voices. We see the world through the eyes of an old woman who seems to be suffering from dementia, young children, grieving parents, suspicious spouses, pacifists, kamikaze bombers, and more.

It was nice to see different perspectives on the Second World War, particularly the opinions of ordinary Japanese, who feel that the Emperor had dragged them into this awful conflict. Serizawa sometimes dealt with issues such as Unit 731 and the infamous “comfort stations,” as well as the zealous young men sent on kamikaze missions, but I must say that I felt she had a tendency to gloss over the atrocities committed by Japan and focus more on the actions of Americans. The Japanese seem only to do bad things when manipulated by their government and the U.S. seems to be equally at fault for Japan’s atrocities. There is an understandable focus on the post-war occupation, for example, with the U.S. soldiers almost demon-like but comparatively little about the Japanese atrocities all across Asia, which any student of history would view as incomparably more brutal. I found this a little frustrating and it extended into the personal realm, wherein the few white characters are viewed rather negatively and the Japanese are more humanised.

On that note, the author often inserted her own political views and in an extremely well-written book these were conspicuously weak parts. The novel (or short story collection) is beautiful in terms of its prose (though occasionally tending towards being overwritten) but in places she would break away to make a rather obvious point through dialogue or internal monologue and I felt these were almost crammed into the text. It is clunky and devoid of the nuance she uses elsewhere. As an author, it’s hard to avoid the temptation but there are definitely more subtle and intelligent ways to make a point.

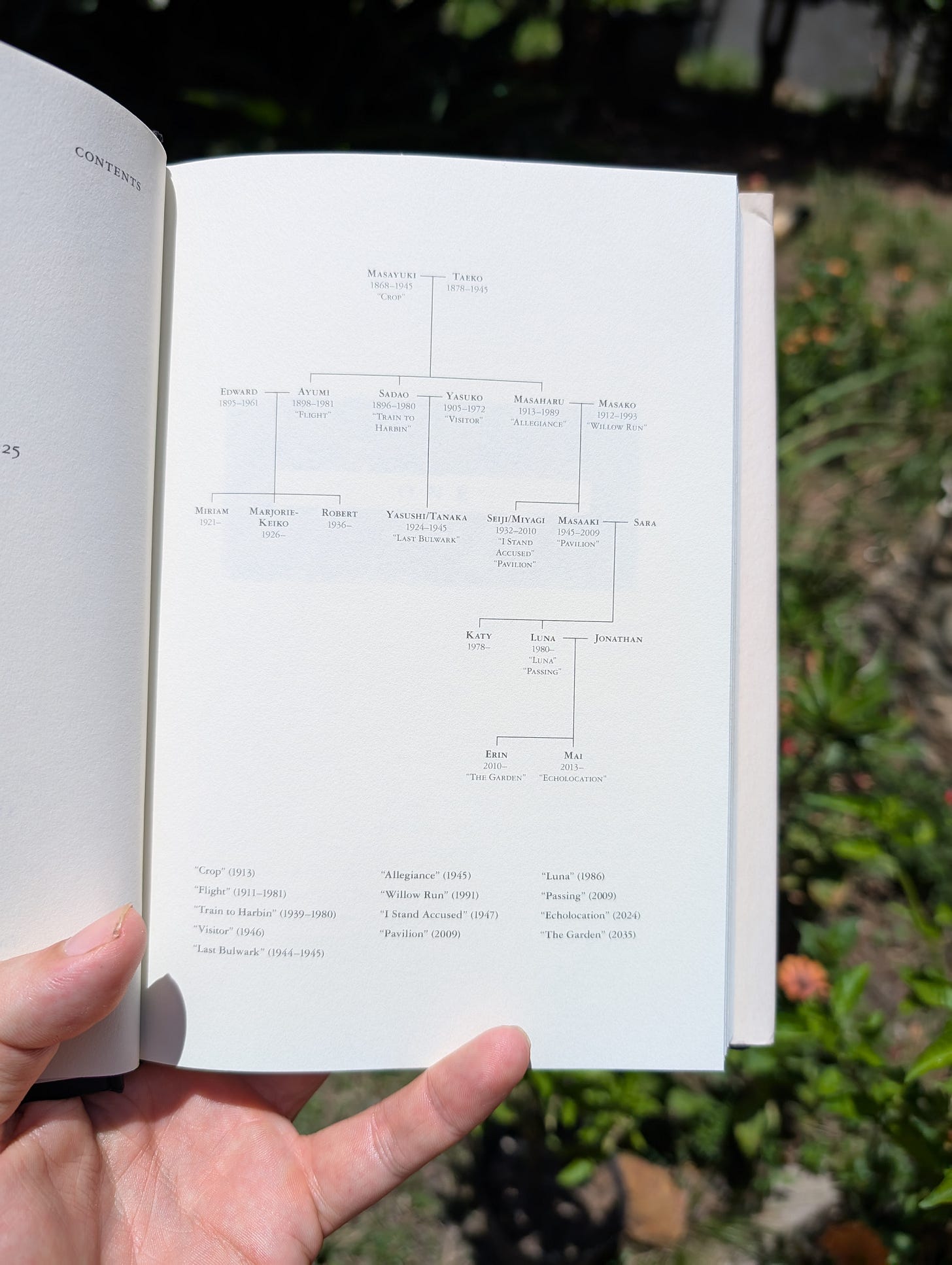

The book begins with a family tree and then is comprised of short stories concerning most of the people listed. In that sense they are connected and there are definitely places where you can see characters’ lives starting to intersect but generally there is no obvious link from one story to the next. However, towards the end of the book you can see connections emerge. These are not causal in any obvious way and a clue to what Serizawa wants to achieve perhaps comes in a discussion between two elderly brothers as they talk about an Argentinian story about a murdered Chinese spy. This is the novel-within-the-novel that I think highlights what Serizawa is attempting here and this relates to the title: Inheritors. We may not know or even think about those who came before us, but we are only here because of them and the massive complexity of their lives unfolded in such a way that our own lives are the way they are. We are all the inheritors of our ancestors’ actions.

Overall, I thought this was a bold and brave book. I respected the author’s vision and the audacity of writing so many stories in so many different ways. I have a massive amount of admiration for how well she puts herself into the shoes of the various characters she writes. I mentioned before an old woman with dementia, but she also writes young men well and is extremely convincing as a small child. She handles the complexities of personal relationships and ethical dilemmas masterfully.

You can find the book on Amazon, Bookshop, or via the publisher. The author’s website is here.

Note: When I review Japanese literature, I’m almost always referring to Japanese literature in translation. However, in this case Asako Serizawa wrote the book entirely in English. She was born in Japan but has spent much of her life in different countries and currently lives in the U.S. I will have another review quite soon, after the release of Sayaka Murata’s next book, Vanishing World. I loved her earlier books and can hardly wait for this one.