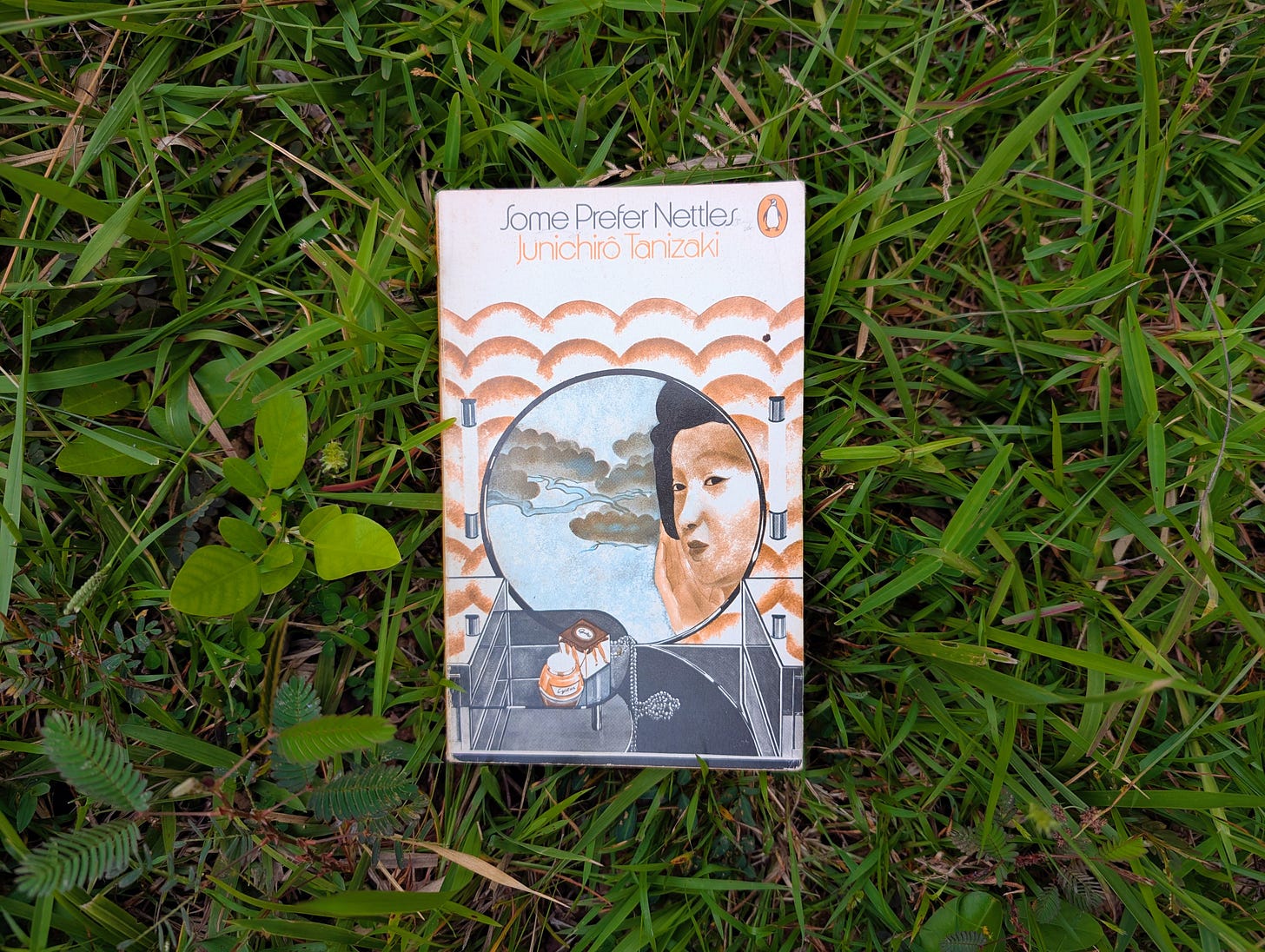

J-Lit Modern Classics #1: Some Prefer Nettles

A look at a great Japanese novel that remains relevant today.

Junichirō Tanizaki’s novel Some Prefer Nettles was published almost a hundred years ago, in 1929, yet it remains astoundingly modern. Were it not for references to Japan’s colonial hold of China, one might mistake it for a work written many decades later. Perhaps this is partly to do with the translation… but even that was done in 1956.

So what makes Some Prefer Nettles so oddly modern? For me, there are a few aspects that are either timeless or modern, including the themes, the characters, the dialogue, and the prose.

For one thing, this is a very short book. The edition I have (published in 1970 and using the 1956 translation) is only 150 pages. There are no lengthy descriptions and the author is quite content to depict a scene and then jump ahead to whatever he next thinks is relevant, quickly summarising everything in between. It is understated, simple, and seems to eschew tedious literary pretensions. You could sit and read it in an afternoon if you wished.

The themes are mostly what qualify the book as modern in spite of it being nearly a century old. The book revolves around a married couple called Kaname and Misako. They have for a long time lived more like friends and they’ve stayed together for the benefit of their son. Misako has a lover that Kaname knows about and we later learn that Kaname also has a prostitute that he regularly sees and may have some love for. They want to divorce but at the same time are reluctant. Both hope the other will ask for a divorce so they can merely agree but neither wants to take the initiative.

The dangers of inaction are discussed quite a bit as both characters act very passively, refusing to do anything that will improve his or her life. Instead, they merely continue unsatisfied for the sake of appearances. It is implied that this is part of the Japanese condition and Kaname believes that in the West it would be far easier to simply go through with a divorce.

All of the main characters here are very familiar with Western culture and they seem to have incorporated Western ideas into their lives to some extent, with this causing some degree of friction against traditional Japanese norms. At the same time, the book also portrays differences between the more modern Tokyo and the more traditional Osaka. It discusses both subtly and quite openly the problems of choosing between new and old as well as local and foreign.

We see this in the two married couples as well as Misako’s father and his wife. The father is proudly traditional and is obsessed with ancient Japanese arts. He trains his wife to be a doll-like figure of classically feminine Japanese values. She is not given much agency and must simply please her husband by learning certain kinds of music and preparing certain kinds of food.

Misako is different. She is a more modern woman, who enjoys the latest fashions and is aware of Western ideas. O-hisa does what her husband tells her and seems to have little sense of self but whilst Misako has some degree of this in her, she is far more liberated and pursues her own interests.

Perhaps it is this quality in Misako that makes Kaname no longer want her as a wife and lover. He mentions several times that she is neither a traditional woman nor what he perceives as the modern Western type. She is neither Madonna nor whore. Again, like many of the themes in this book, it is explored subtly at first through demonstration and then more directly at later points. Kaname recognises this weakness in himself and discusses it but he cannot seem to move beyond it.

I think all of this makes the book highly relevant now. Whilst it shows a small group of people in Japan in the 1920s, those themes and discussions are pretty relevant to much of the world’s population now. We all feel some degree of confusion between the old and the new, and we exist in a world where values are changing rapidly and cultures are impacting upon each other, eroding old ideas and constantly supplying new ones. It can be overwhelming and there is often the sense of loss even when the excitement of something new comes along. We know too much and we want too much and so we cannot possibly have everything we desire.

The situation between the married couple (Misako and Kaname) may seem slightly absurd but it nonetheless highlights a real struggle for many people: indecision. People of all backgrounds often find themselves staying in unhappy situations simply because they fear change—and not just the negative outcomes for themselves but how their actions may harm others. This leads them to continue as they are, which is often more damaging than the temporary pain that comes from making a change.

The main characters in this book are all to some degree engaging in performance (which is a theme made quite explicit when they visit a puppet theatre and discuss performances). They must present false versions of themselves to the people around them and ultimately they seem to lose themselves in this performance. Over time, they become less sure of what they want and more incapable of seeking it.

The prose is incredibly modern too. It reminds me a lot of another book from that decade: The Great Gatsby. The characters speak with great wit and yet there is a lot of realism. These are not artificial witticisms but rather than normal sort of joking between people that we engage in even today. There is no flowery, literary language. When the parents speak to or around their child, it is highly believable. Again, this sets the book apart from most classics, modern or otherwise. It makes it accessible and enjoyable. For me, it made the philosophical and cultural issues all the more interesting.

I read a lot of Japanese novels but mostly I focus on new ones. (See my series of reviews here.) This book was one of the best that I’ve read in a long time and I thought I’d write about it here in case others were interested in finding a copy. It is a classic but as I’ve said it feels very, very modern. It contains much wisdom that might help people dealing with the issues described (inaction, indecisiveness, a split between old and new, etc).

I wrote recently about why people in the West are turning to Japanese fiction and I think this book will appeal for the reasons I described. You can read it here: