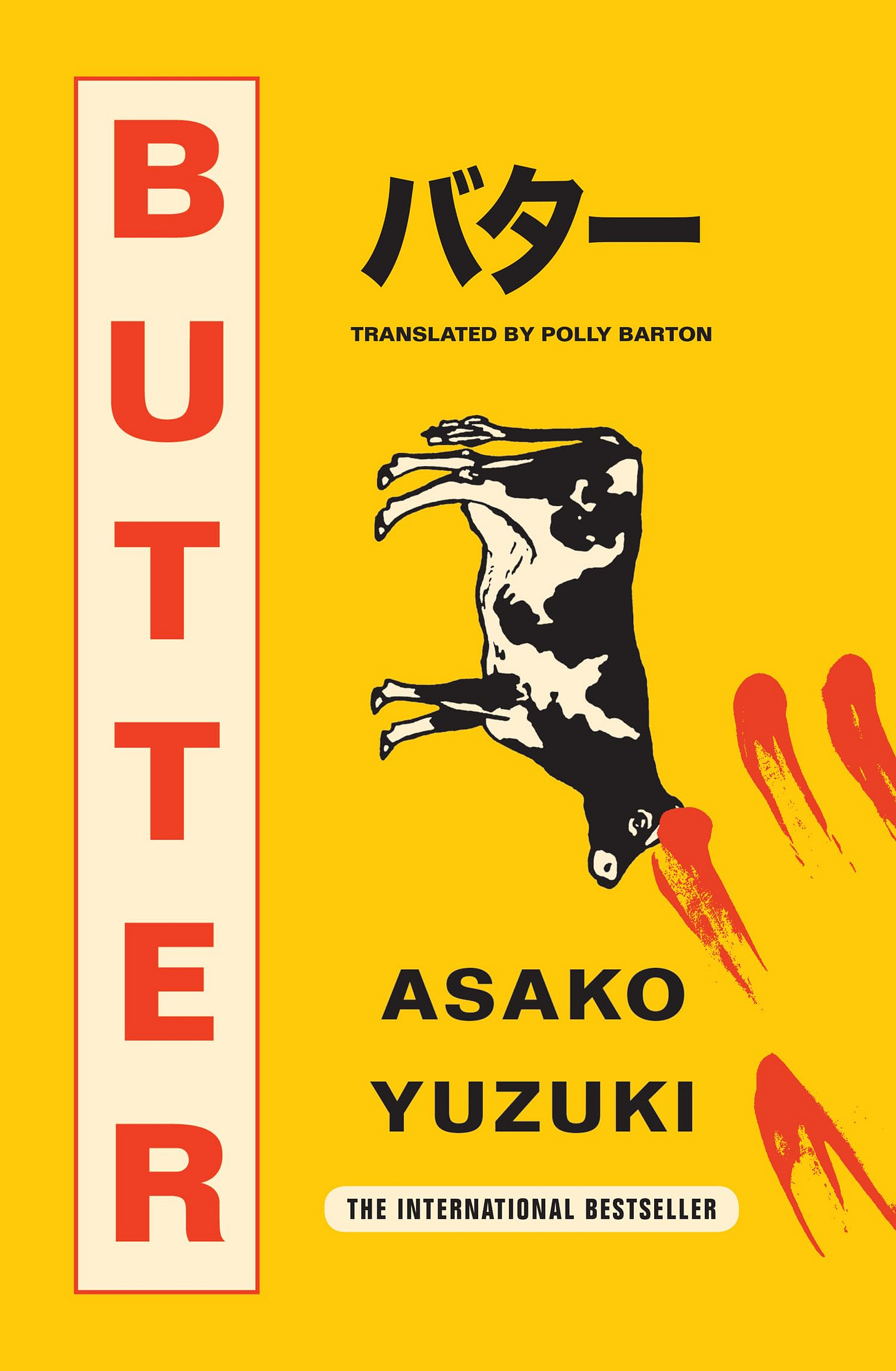

How Not to Write a Novel: A Review of Butter by Asako Yuzuki

A new novel falls flat but provides important lessons for novelists.

One of the most fundamental rules of fiction, and something that almost any good writer learns before even starting their career, is the idea that you must show, not tell.

As the above meme suggests, good literature does not include characters saying “A bad thing happened to me, so I feel sad.” Instead, we see the bad thing and we see the changes in the character’s actions or speech that make us understand their emotions. Likewise, you do not tell your reader, “Poverty is difficult.” You write a novel that shows people struggling with poverty. If you are a good writer, the message is clear.

Chuck Palahniuk calls this “big voice.” Your “little voice” is like a camera showing the characters’ lives and your “big voice” is when the author speaks directly to the reader. “yes, a small amount of big voice goes a long way,” he says, but “keep your big voice philosophizing to a minimum.” In the same book (the wonderful Consider This), he advises writers to “Trust your readers’ intelligence and intuition, and they will return the favor.”

This is Writing 101. It is a fundamental rule underpinning genre fiction, literature, and even TV and movies. Writers that fail to achieve this create dull, uninspiring works that just don’t ring true. They end up producing books that are more like manifestos than novels. This is precisely why utopian and dystopian fiction is almost always terrible. In such works, writers try too hard to put across their ideas rather than creating characters, showing action, presenting a landscape, or building dialogue. Everything in their work exists merely to present their ideas. The story and characters always seem hollow because they were created as props to make a manifesto more interesting.

That’s the fundamental problem with Asako Yuzuki’s Butter, which got its English-language release earlier this year. It is ostensibly the story of a journalist who becomes interested in an apparent serial killer, an overweight woman who seduced and then killed a number of lonely men.

This is a fine idea for a novel and there are parts of it that are of minor interest, but unfortunately Yuzuki has picked up on this story purely because it seemed a perfect vehicle for her to make a few rather obvious complaints about the challenges of being a woman in modern Japan.

I’ll state here and now that I actually agree strongly with some of the complaints she makes, namely that there are ridiculous and dangerous beauty standards placed upon women and that some workplaces can be hostile towards female employees, with men taken more seriously and being more likely to get promoted. My objections to this book do not stem from a disagreement over her views.

Alas, no matter how much I agree with someone’s ideas, I still want to read a decent novel, and Butter falls far short in that respect. In fact, it falls disastrously short and it took me several weeks to read this book because I simply dreaded picking it up and slogging through the next few pages.

Modern Japanese feminist literature is one of my favourite genres right now, and it has been for several years. I love reading works like Diary of a Void by Emi Yagi or Breasts and Eggs by Meiko Kawakami. These books intelligently and artfully show life from the perspective of someone very different to me, and I learn a lot from these stories. I think that’s one of the greatest attributes of fiction—it puts you in someone else’s shoes for a while. But they were works of art that included social criticism.

Butter is the very opposite of that. The author has not attempted to present a good story that happens to include some of the difficulties facing women in Japan, but rather she has listed everything that pisses her off in life and then woven her complaints carelessly into a silly story. Every scene and every bit of action or dialogue is used as an excuse to explain why it’s hard to be a woman.

The result is a book that one must suffer through rather than enjoy. The author and her characters love explaining everything, making the reader feel like they are being talked down to. She will not only show you the protagonist, Rika, struggling with something and allow you to realise that it is because of her guilt over her dead father, but instead the author will tell you this plainly and then the character herself will say it again. She will not show female characters being ignored or otherwise badly treated by men and let you understand by yourself that these are problems. She will tell you several times. Key points are repeated pointlessly and nothing is ever left to the imagination.

Again and again, we are told “It’s difficult to be a woman” and “It’s okay to be overweight.” These are fine messages to present… but either choose to do so through fiction or write an article or essay about it. If you attempt to produce a novel, then let the characters, action, plot, and dialogue bring the reader into your ideas. Don’t beat them over the head with these ideas.

There are a handful of positives. There are long passages about cooking, which are quite amusing, and I actually did learn a few things about cooking. These passages are silly and indulgent, but in a good way. They remind me of the unbridled enthusiasm of Nabokov. However, they do not detract from a lazy, repetitive, overly long novel that has all the depth and literary merit of a picture book for toddlers.