Cats and Murakami: Do Felines Really Appear in All His Novels?

A look at the novels of Haruki Murakami and their depictions of cats.

Murakami is often known by both his fans and critics for the repetitive tropes in his novels. This has led to something termed “Murakami bingo.” Readers note that his books often feature a single male protagonist, wells, jazz music, ears, dreams, women’s breasts, and of course cats.

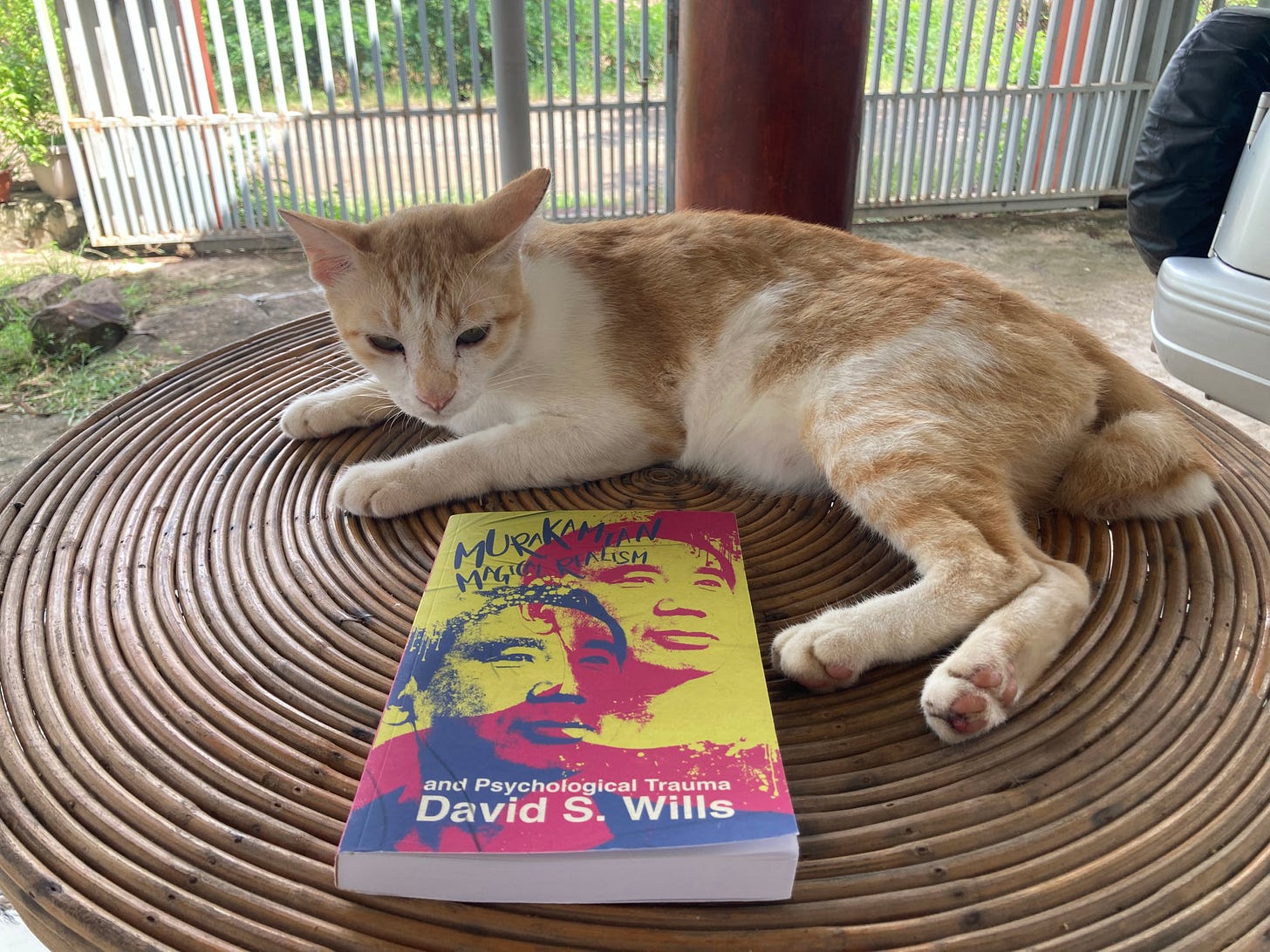

In online Murakami fan communities, people tend to fixate on the most obvious tropes and you often see fans posting pictures of cats beside wells. In fact, cats seem to be so synonymous with Murakami’s work that you might even see a picture of a cat beside a book with various people commenting, “Oh, just like Murakami!”

But are cats really all that common in his work? Let’s explore…

Hear the Wind Sing

In Murakami’s first novel (or is it a novella?), there aren’t many references to cats but those that you can find are quite significant. The protagonist tells us that he visited a psychologist as a child and quite oddly he says the man was “like a timid cat.” This seems unimportant until a few paragraphs later things get weird and the psychologist starts to explain the nature of the universe and how things only exist because of communication. To illustrate, they engage in word association:

We went on from there to free association.

“Say something about a cat. Anything.”

I slowly rotated my head, pretending to be thinking.

“Whatever comes to mind.”

“It has four legs.”

“So does an elephant.”

“It’s a lot smaller.”

“What else?”

“It lives in people’s homes and kills mice when it feels like it.”

“What does it eat?”

“Fish.”

“How about sausages?”

“Sausages too.”

We carried on in that vein.

The doctor was right. Civilization is communication. When that which should be expressed and transmitted is lost, civilization comes to an end. Click…OFF.

How is this important exactly? Well, it has been argued that this idea of word association is actually the very core of meaning inside Murakami’s fiction and given that this first example of that begins with a cat bestows an unusual level of important on this particular creature. (See Mathew Carl Stretcher’s book Dances with Sheep for more on this.)

Later in the novel, we find out that the protagonist had killed cats as part of his studies:

I told her about the cat experiments we carried out. (Of course, I lied that we never killed them. That we were just testing their brain functions. In fact, over the course of a mere two months, I was solely responsible for snuffing out the lives of thirty-six cats of all sizes and shapes.)

Is there a connection between the guilt he feels over the deaths of these animals and the fact that he demonstrates existence and non-existence through a word game beginning with “cat”? I have my opinions, but in the world of Murakami, nothing is ever clear.

One final reference is in this part:

Hartfield detested so many things: post offices, high schools, publishing houses, carrots, women, dogs—the list is endless. There were only three things that he liked, namely, guns, cats, and his mother’s cookies.

This is about Derek Hartfield, the only named character in the book. He is an American author (not a real one) and very clearly based on Kilgore Trout, from the books of Kurt Vonnegut. Note that one of the only three things he likes is cats… Why? It is tempting to think of this as Murakami inserting himself into the text but Murakami is nothing like Hartfield. In fact, the only similarity in this list is the affinity for cats.

Pinball, 1973

In Murakami’s next book (again, is it a novel or a novella?), cats appear in various ways and for various purposes. The first reference is to a fading smile like the Cheshire Cat’s, and the next is a quite beautiful simile:

The undulating hills resembled a giant sleeping cat, curled up in a warm pool of time.

We saw that Murakami had included a made-up author (Derek Hartfield) in his first book and he did that here again with a number of imaginary essays. One of them asks the question “Why does a cat wash its face?” Later, there is a reference to a cat dying when two twins (who speak as one) ask the protagonist, “Have you ever seen a cat die of blood poisoning?” After that, we get the following bar conversation:

“I do have a cat, though,” J added. “She’s getting on, but she’s still someone to talk to.”

“You talk to it?”

J nodded several times. “Yeah, we’ve been together so long we know each other pretty well. I can tell what she’s feeling, and she’s the same with me.”

Cigarette between his lips, the Rat grunted, impressed. The jukebox clicked, and Wayne Newton gave way to “MacArthur Park.”

“Hey, what do cats think about, anyway?”

“Lots of stuff. Just like you and me.”

“Poor things,” the Rat said, laughing.

J laughed too. “She’s one-armed,” J added after a long pause, rubbing the countertop with his fingertips.

“One-armed?” the Rat asked.

“The cat. She’s a cripple. Four winters ago she came back one day all covered in blood. Her paw was smashed so bad it looked like strawberry jam.”

The Rat set his beer down on the counter and looked square at J. “What happened?”

“Beats me. I thought maybe she’d been run over. But it was worse than that. A car tire can’t do that to a paw. It looked as if it had been crushed with a vise. Flat as a pancake. Must have been a prank.”

“No way!” The Rat shook his head several times. “Who in hell would do that to a cat?”

J tapped his unfiltered cigarette on the counter and lit it.

“You’re right,” he said. “No point smashing a cat’s paw like that. She’s a sweet cat, too, no trouble to anyone. So what’s to be gained from mangling her paw? It was a senseless, evil thing to do. Still, evil like that is everywhere in this world, mountains of it. I can’t understand it, you can’t understand it. But it’s there, no question. You could say we’re surrounded by it.”

With his eyes on his beer glass, the Rat shook his head one more time. “Well, it doesn’t make sense to me.”

What do we make of all this? It’s hard to say for sure but note how similar the appearance of cats is in each of these two books. They are used in reference to non-existent authors (whom the reader is meant to think are real) and also to discuss cruelty and death. These books were very strange discussions of loneliness and trauma, so the cats seemingly stand for something bigger in a somewhat abstract sense. Murakami put a lot of his own early life into these books, so is it possible that he had hurt or killed one or more cats as a boy? (We certainly know that he witnessed his father abandon a cat, as detailed in a 2019 essay.)

But what about the comment, “she’s still someone to talk to”? This is the most telling because it connects fairly obviously to the one other cat reference in the book. The protagonist often goes to a pet shop to look at or play with the cats that are sold there. Nothing really comes of it but it clearly speaks to the main theme of loneliness. He has few people to talk with but he connects deeply with the cats and in turn they seem truly grateful for his attention. In a very dreamlike book, it is also notable that the protagonist says, “the two cats stared at me, as if I were a fragment from their dreams.”

A Wild Sheep Chase

Cats appear again in Murakami’s third novel and this time they seem more obviously significant. In the second chapter, where we learn about the marital problems of the protagonist, the cat is in the background but its actions are described. It is a part of their life together, like a child. Later, when their marriage is entirely over and the protagonist is completely alone, the cat is his companion, as it had been for J in the previous book.

In fact, J returns in this book and we learn that his cat lived to the age of 12 and then died. He talks about burying it in a nice place but notes that it probably had no meaning to the cat. He then says, “Even if a person had died, I wouldn’t have been as sad. Does that sound funny?” This is an unusually open comment on the importance of animals and their connections to humans.

Is that the sole purpose of cats in this book? To show how lonely a person is? Here and elsewhere, cats seem to highlight human loneliness and isolation. At one point, the protagonist flat-out tells us that all he has in life is his cat… a frail cat that can barely eat. We learn in a series of long paragraphs all about the cat’s health problems and perhaps this is intended to show us that the cat is, for the protagonist, basically like his child. He knows everything about this creature and cares for it more than anything else in the world even if it is unable to keep itself alive without substantial human effort.

Probably the most important aspect of cats in this novel is the discussion between the protagonist and an employee of a man known only as The Boss. We learn that he hates cats, which makes sense given that he seems to be a sort of embodiment of unseen evil.

Later, the cat features as part of a discussion on the importance of names. Despite being so central to the life of the protagonist (who is unnamed), the cat has no name until he is named “Kipper.” You can learn more about Murakami and naming conventions in this essay:

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

We have now seen that cats were extensively referenced (but sometimes for mysterious purposes) in Murakami’s first three books. So what about the fourth one?

Interestingly, cats aren’t mentioned much in this book. They appear as similes twice (The protagonist wants to read a newspaper like a cat lapping up a dish of milk…) and later we learn that he had a wife and cat but that they both left him. Wives leaving husbands and cats disappearing will be a very, very common trope throughout the first half of Murakami’s writing career.

Norwegian Wood

Norwegian Wood is often said to be the least Murakamian of Murakami’s books. In this novel, he deliberately abandoned most of his stylistic quirks and many of his favoured themes. But what of cats?

Cats do appear and again they serve similar functions. They are similes (“Midori put her guitar down and slumped against my shoulder like a cat in the sun”) and they die, leaving people devastated. We learn that one character never cried when her mother died but “cried all night when [her] cat died.” They sometimes just appear as part of the scenery—something to be noted lying in the sun. Elsewhere, we have a porcelain beckoning cat and a parrot who is deathly afraid of cats. Sometimes they just exist as the backdrop to a conversation, with characters patting or watching cats as they talk.

But perhaps of most interest is that when the protagonist writes a very important letter to Naoko, his love interest, the first thing he mentions is the cats outside his window and he explains their lives to her. He does this later in conversation with another girl he loves.

Dance Dance Dance

This novel is a continuation of the story set out in the first three books. Those are considered a trilogy but generally Dance Dance Dance is not believed to turn it into a tetralogy because the story moves in a very different direction. Even so, we have the same protagonist and we learn about how his life has moved on, which includes the death of Kipper, the cat we met in A Wild Sheep Chase. He gives him a burial and clearly goes to some effort but there isn’t the sort of emotion we would expect, given how cats were treated previously. “Sorry, I told the little guy, that’s just how it goes.”

There aren’t many other references to cats but there is one particularly important one. One particularly important character confesses to some awful things from his past, including murdering four cats. He is worried that he will go on to murder his wife. We might easily overlook this except that killing cats has been mentioned several times in earlier books. Again, that raises the question of why it is on Murakami’s mind.

South of the Border, West of the Sun

There are no significant cats in this book but nonetheless they do appear and serve a purpose. Right at the very start, we learn that they are a part of normal suburban life in Japan. The narrator describes your average suburban home and says, “And most everyone had a cat or a dog.” Talking about the girl he loved as a child, cats are mentioned second in a list of things they had in common: “The more we talked, the more we realized we had in common: our love of books and music; not to mention cats.”

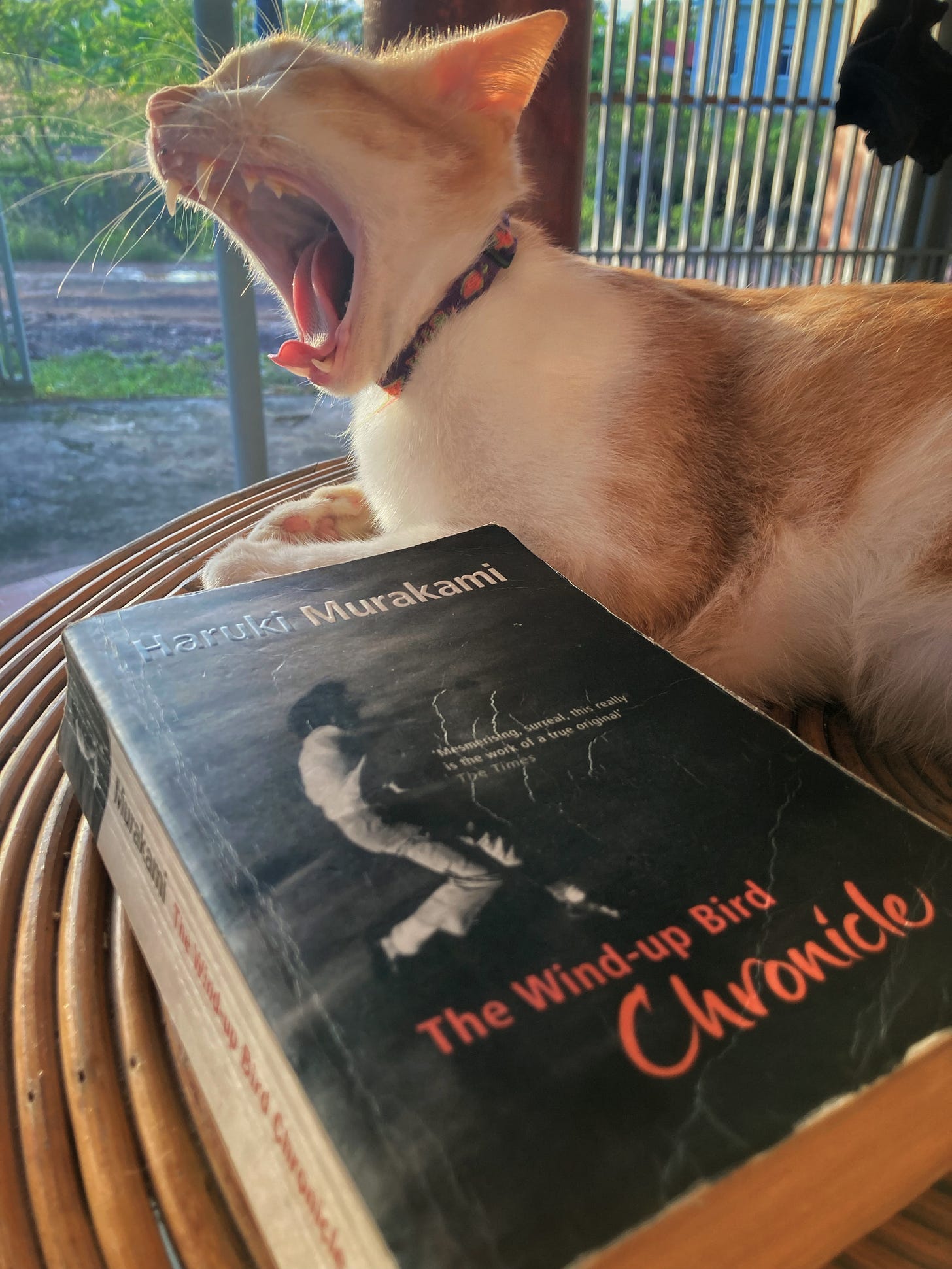

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

This is probably the book that first made Murakami famous for writing about cats. It is his masterpiece, as I’ve said many times on this blog, and it quite strangely utilises a cat to set the story in motion. Reversing the order of a previous novel, wherein a man’s wife leaves him and then his cat, in this story the cat goes first.

In a sense, then, the cat is merely a plot device… but that’s perhaps reductive because whilst it exists largely to start the novel and bring about a strange chain of events, it is not entirely without other importance:

So now I had to go cat hunting. I had always liked cats. And I liked this particular cat. But cats have their own way of living. They’re not stupid. If a cat stopped living where you happened to be, that meant it had decided to go somewhere else. If it got tired and hungry, it would come back. Finally, though, to keep Kumiko happy, I would have to go looking for our cat. I had nothing better to do.

We have here a little insight into the protagonist and I think also the author. He simply likes and respects cats.

We saw in an earlier book that the cat was unnamed and it seems that they mostly were. This was obviously part of Murakami’s early philosophy on the unimportance of naming things, but this time around the cat is named Noboru Wataya. That is the name of Kumiko’s evil brother, the antagonist of the book and seemingly the embodiment of everything wrong in the world according to the author. But why name a cat after such an evil person? That is explained here:

“How does the cat remind you of him?”

“I don’t know. Just in general. The way it walks. And it has this blank stare.”

It seems like a cop-out but the phrase “it has this blank stare” is telling. Later, we learn about how the real Noboru Wataya is like a politician—blank but able to adopt whatever policy is necessary to gain power. The blankness hides malevolence.

To connect the cat with an evil man is strange of course but Murakami’s books are seldom straightforward. This connection does not speak to the evil in cats at all and again we soon learn about the connection between humans and felines:

I realized that Kumiko was crying. It was understandable: Kumiko loved the cat. It had been with us since shortly after our wedding.

Then later:

“I want you to understand one thing,” said Kumiko. “That cat is very important to me. Or should I say to us. We found it the week after we got married. Together. You remember?”

“Of course I do.”

“It was so tiny, and soaking wet in the pouring rain. I went to meet you at the station with an umbrella. Poor little baby. We saw him on the way home. Somebody had thrown him into a beer crate next to the liquor store. He’s my very first cat. He’s important to me, a kind of symbol. I can’t lose him.”

It’s not just Kumiko. The protagonist too loves that cat and cats in general:

“Always had one when I was a kid. I played with it constantly, even slept with it.”

The cat continues to propel the story forward by bringing the protagonist to different places and introducing him to different people through his search for this missing creature. This is a weird book though and it quite often drops parts of the story or characters and then reintroduces them later. That is true of the cat, which suddenly reappears. This is a year later and long after a very important character tells him that the cat will never be found. Why? What does this signify and is it merely another plot device? It is noteworthy that the cat is now given a new name: Mackerel. He is no longer named for the book’s antagonist.

Is this the same cat? It seems a silly question but this issue is raised and we never really know for sure. Its tail is slightly kinked and a character with supernatural abilities seems to doubt that it is the same one. Of course, in the Murakamian world, we are never going to find a clear answer and so we will all have to make up our own minds.

Many times in this book, characters cross from the real world into the metaphysical realm. (Arguably, this happens in all Murakami’s books.) Interestingly, when this happens and we are uncertain of it, cats again appear:

Cats lay everywhere—beneath the windows, in the doorway—watching me with weary eyes.

One final point here as this has gone on too long already… When we meet the possibly evil character of Ushikawa, he says, “Tell you the truth, I’m not very good with cats.” Is this like when “The Boss” hated cats—a sign that cats are good and bad people simply cannot like them? Given how the good characters do like them, it is tempting to believe this.

Sputnik Sweetheart

For the first half of this short novel, there is no mention of cats at all. How strange! Then, randomly, we hear the story of an old Greek woman who dies and is eaten by her cats. This leads to a story… “Speaking of cats,” Sumire had blurted out, “I have a very strange memory of one.” She goes on to tell about how as a child her cat went up a tree and never came down. It literally disappeared. This is significant because Sumire herself will disappear without a trace but we also get the usual explanation of the emotional bond between human and feline:

“I never had a cat again. I still like cats, though I decided at the time that that poor little cat who climbed the tree and never returned would be my first and last cat. I couldn’t forget that little cat and start loving another.”

Why is this important? We know from interviews that Murakami had a cat as a child but does not have one as an adult. Perhaps he too lost his cat in some mysterious way and then could not bear to love another. He evades the question when asked, as he does with most important issues.

Kafka on the Shore

This book is the only one that rivals A Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in terms of making Murakami famous for his depictions of cats. In fact, by now perhaps it is even more famous…

What people often get from this book is that it’s about talking cats and even some of the promotional text for his books mention Kafka on the Shore as featuring talking cats, but this is not quite true. It is simply that one of the characters, Nakata, has the ability to converse with these animals. They do not seem able to speak with other humans.

From the cats, we get yet more insights about names:

“I forget my name,” the cat said. “I had one, I know I did, but somewhere along the line I didn’t need it anymore. So it’s slipped my mind. […] Cats can get by without names. We go by smell, shape, things of this nature. As long as we know these things, there’re no worries for us.”

Nakata uses his ability to hunt for lost cats, which we can see is a reoccurrence of that old trope. And just as in other books, these cats and their appearances and disappearances tend to function as plot devices and a means of exposition. Here, the cats help us to understand Nakata is missing his shadow and that he had an accident when he was young.

All in all, the use of cats here has some resemblance to earlier novels but at the same time it is quite different. Cats are characters to a limited extent rather than mere devices. They are often used for comical purposes, too. They raise questions about how much cats can know of the human world and give insight into the possibilities of the cat world.

There aren’t too many physically awful things in Murakami’s novels (the flaying of a human in The Wind-Up Chronicle being one oft-cited example) but certainly the vivisection of cats in this book is particularly awful. Did Murakami allow these cats to speak and have personalities so this would affect the reader more? Did he include this part of the book to show the awfulness of animal cruelty? Does this relate to earlier novels, where we see people’s guilt over killing or harming cats? It’s hard to ignore the similarities. When the character of Johnnie Walker kills cats slowly and consumes them, it might possibly be a Murakamian commentary on animal testing or modern science or just man’s capacity for cruelty. Nothing in this book has a clear meaning, so it’s impossible to say with any degree of certainty.

After Dark

There are no cats mentioned in After Dark until chapter 9, when they appear briefly:

“There’s a tiny park down the street where the cats like to gather. We can feed them your leftover tuna-mercury sandwiches. I’ve got a fish cake, too. You like cats?”

Mari nods, puts her book in her bag, and stands up.

They go to the park and feed and pet cats. There, they discuss cats and dogs and unsurprisingly determine that “cats are better.” They talk about other things but cats keep on appearing. That’s all for cats in this book, making it the least cat-heavy Murakami novel so far.

1Q84

Cats appear early in this long novel but not in a significant way. We learn about spaces being big enough for cats and as with so many of his books we see a cat sleeping in the sun. There is an allusion to the old “Do we give cats and dogs names?” question as well but it’s not discussed unlike in earlier books. (In fact, I feel this novel sees Murakami deliberately refer to earlier works in subtle ways.) Unlike so many people mentioned thus far, Aomame (one of the book’s two protagonists) did not have a cat when growing up. This is mentioned no doubt to highlight how sad her childhood was.

Almost halfway through the extremely long book, the reader might ask, “Where are all the cats?” and that’s when we start seeing them. Oddly, they appear in stories within the story. One is called “the vegetarian cat who met up with the rat.” Another is about a town populated by cats. In each case, we are given a story about cats and then told there was no point to the story!

No point, really. I suddenly remembered the story when we were talking about luck before. That’s all. You can take whatever you like from it, of course.

Of course, the reader will have his own inferences, particularly when “the town of cats” is repeated several times. How could it not be of importance? We also have reference to Chekhov’s gun, which of course suggests that nothing is mentioned without meaning.

I thought it was quite amusing that in this book Murakami actually named a chapter “Time for the cats to come.” He is clearly aware of his reputation and habits and the fact that he’d not included many by this point.

By the way, if you’ve not read this novel and are interested in “The Town of Cats,” it is available as a standalone excerpt from The New Yorker.

One final point is how many times Fuka-Eri is described as being like a cat—like a wounded cat, like a contented cat, etc. This is a very, very repetitive novel and this image keeps re-occurring. The phrase “like a wounded cat” appears 13 times!

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Here we have it… Finally, a novel with no cats!

Cats are mentioned four times but only as references or images. They do not physically appear.

Shiro was usually quiet, but she loved animals so much that when a conversation turned to dogs and cats, her face lit up and the words would cascade out from her.

“That’s a great question,” Haida said, and smiled quietly. The kind of smile a cat gives as it stretches out, napping in the sun.

So, like a dying cat, I’ve crawled into a quiet, dark place, silently waiting for my time to come.

The bellboy grinned and softly slipped out of the room like a clever cat.

Killing Commendatore

In contrast to the previous novel, cats are mentioned in the first chapter of this one, although they are not of huge significance. We learn that the house that will be the main setting for the novel has a lot of cats around it. This is strange because although most of the book takes place there, we seldom encounter them after this point.

Once again, characters are described as cat-like:

Like some large cat taken to a new place, each movement was careful and light, his eyes darting quickly around to take in his surroundings.

She’s a very quiet girl, like a bashful cat.

Mariye kept studying Killing Commendatore by herself for a while, then finally, like a very curious cat

The Commendatore scratched behind his ear with his little finger. Just like a cat will scratch behind its ear before it rains.

And, just as before, she had a sour expression on her face. Like a cat whose dish has been whisked away halfway through its meal.

Long Face did not move a muscle as I approached. He seemed rooted to the spot. Like a cat in the headlights.

A chapter has “cat” in the title (“Curiosity Didn’t Just Kill the Cat”) but there are no cats mentioned in it. We have reference to the Cheshire Cat’s smile again, which had been noted in his second book.

Very late in the book, we get this unexpected paragraph:

I ransacked my store of memories. Komi and I had raised a pet cat. A smart black tomcat. We named it Koyasu, though why we gave it that name escapes me. Komi had picked it up as a kitten on her way home from school. One day, however, it disappeared. We scoured our neighborhood looking for it. We stopped countless people and showed them Koyasu’s photograph. But in the end the cat never turned up.

How interesting that once again a married couple has lost and looked for a cat. Clearly this is something of importance to the author. This part goes on, though, in a different way. Although the idea seems so similar to his earlier works, now it is all about memory. He is trying to bring the cat to mind, to make it real. This book is all about collective memory and Japanese history, so it is a comment on trying and failing to recall the past.

And one more thing… Several times, birds are described as being like cats with wings. Why? On that point, I have absolutely no idea. I know in Chinese that owls are called “cat-headed eagles” but I’m not sure about the Japanese for these creatures.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls

What of Murakami’s latest novel? (I reviewed it here a few months ago.)

Unsurprisingly, given that this book is partially a rewriting of an earlier novel, there are old tropes revived. A young boy and girl bond over cats. This leads to the following observation, which perhaps explains much of what we’ve seen so far in this essay: “People who love cats naturally like other cat lovers.”

How many times have we seen that happen? Almost as many as we’ve heard this: “like an old cat napping in the sun.” Murakami does like to repeat himself, doesn’t he?

I think this is a first, though:

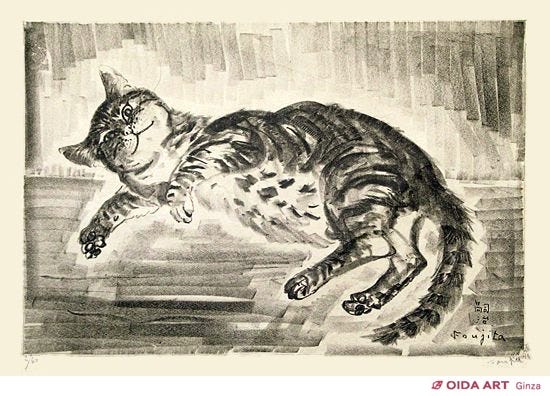

On the wall behind her was a small painting by Léonard Foujita of a cat stretching, in a sturdy-looking frame.

I cannot recall from these books another painting of a cat. A quick Google search suggests it’s this one:

Again, there are many examples of people being “like cats.” Someone has hands like a cat. (Do cats even have hands?) Others have cat-like reactions.

There’s a man living on a mountain with cats. Is this a reference to Killing Commendatore?

There’s a library surrounded by cats. Is this a reference to Kafka on the Shore?

You may think I’m being ridiculous here, but actually Murakami references back to earlier in novels in ways just like this, so it’s quite possible.

Occasionally, we get close-up looks at cat families and cat behaviours. For example:

After warming my chilled body at the coffee shop, I didn’t go right home but took a detour to the library, and went around to the rear garden to see the cat family. To avoid the weather they’d set up house underneath an old porch. Someone had made a little bed for the cats with a cardboard box and an old blanket. The mother cat wasn’t cautious around people (the women in the library gave them food every day), and even when I got near, she merely glanced at me but didn’t tense up. The tiny kittens, their eyes still not fully open, relied on their sense of smell to gather, like larvae, around their mother’s nipples. The mother cat, eyes narrowed, watched her babies lovingly. I watched this from a way off, never tiring of the scene.

This cat family is meant to give us some insight into a character but given how new this book is, I will say little because I don’t want to spoil it.

Conclusion

Cats appear in one way or another in all fifteen of Murakami’s novels. Only in one book are there no cats at all, but even there he uses them as imagery.

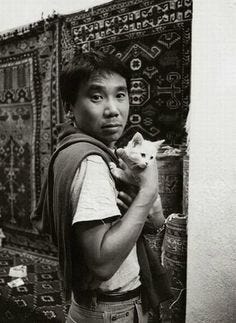

The author says famously little about his life, especially his childhood and relationships. However, in various interviews he has acknowledged loving cats. In Novelist as a Vocation, he spoke of having cats as a child and then during his early married years. In an interview with Deborah Treisman in 2019, he was asked about music and replied: “Music and cats. They have helped me a lot. […] I go jogging around my house every morning and I regularly see three or four cats—they are friends of mine. I stop and say hello to them and they come to me; we know each other very well.” He says he does not currently have any cats and unsurprisingly claims “I don’t know whether they have any other significance [in his work].” Knowing Murakami, if he did know, he wouldn’t say. But therein lies the magic…